A decade and a half ago, when I decided on a whim to get a Masters in Afro American Literature at UW-Madison, I decided to write my thesis on Toni Morrison’s work. I’d first come to Morrison’s novels when I lived in Chattanooga, TN and was a student at UT-Chattanooga. A new bookstore had just opened, creating a space for used books, used cds/cassettes/albums and video-games. On my first visit to this store, I was completely overwhelmed at the sheer numbers of books. So, to mitigate my pressing sense of claustrophobia, I decided to focus on book spines. My eyes landed on The Bluest Eye & I was intrigued. What is this story about one eye? Is it a murder mystery? A detective story? Who is this Toni Morrison?

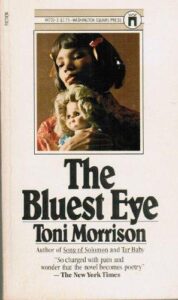

I was perhaps 21 or 22, maybe 23, and I’d never heard of Toni Morrison. In fact, I had never really heard of any living Black writers or many non-living Black writers. I pulled the book from the shelf, studied the cover, and put it back, moving on until I hit the “B” section and found a new intriguing title, If Beale Street Could Talk. I didn’t know who James Baldwin was but I recalled a movie I’d seen, “The Women of Brewster Place”, and, confusing these two titles, purchased the book. Home, I couldn’t get the Morrison title out of my head or the odd cover, but Baldwin’s novel enticed me, so I spent the summer reading all of the novels of his that I could find at the used bookstore. And when I was done reading Baldwin, I was still haunted by that Morrison title. I raced back to the bookstore in search of The Bluest Eye.

It was a curious cover; a Black child holding a White porcelain doll; both the child and the doll appearing old, wizened. I want to say I read the short novel in one sitting, but who can read Morrison in one sitting? I didn’t devour Morrison’s sentences; I savoured them. “Quiet as its kept, there were no marigolds in the fall of 1941.”

It was a curious cover; a Black child holding a White porcelain doll; both the child and the doll appearing old, wizened. I want to say I read the short novel in one sitting, but who can read Morrison in one sitting? I didn’t devour Morrison’s sentences; I savoured them. “Quiet as its kept, there were no marigolds in the fall of 1941.”

Yesterday, I listened to a writer who was born in 1970, the year The Bluest Eye was published, say that she’d read the novel in high school. I was quite shocked and, honestly, jealous. Who were these Atlanta teachers who gave students a book by a living writer? By a Black writer, living or not? It wasn’t until 1997 that I read a Toni Morrison novel as part of a class assignment; this was after I had taken a course called African American Literature, in which we mostly read books by Black men, most of them not living. In a political science course on women and politics, we read Beloved. The teacher was White, all of my peers were White. Many of them boycotted the book after reading the first chapter, saying the teacher only selected it to make me, the one Black student, feel seen, which was absurd since the reading list was decided before students were enrolled. Most of them refused to show up after that first day, so the teacher sneakily moved the book to later on the schedule. The teacher cried in class while talking about the novel and apologized to me about slavery. I was still thinking about Sula, which I’d read after finishing The Bluest Eye and Song of Solomon, which I read after finishing Sula and Tar Baby, which I read after finishing Song of Solomon. I was intrigued by Morrison’s sentences, her paragraphs, her ability to make the past ALIVE and RELEVANT. I was thinking about my parents, how they had tried so hard to raise me as what I was–a Black child–and how I refused them, how their stories felt oppressive, how when they talked to me of the past I felt as if the clouds were cotton pressing down on me, pounds and pounds of cotton clouds choking me out; how I came, later, to understand that sensation as re-memory, how I came to understand that term, re-memory, by reading Beloved in that political science course, but how I wouldn’t know the term itself until I was a graduate student, three times over.

Violence. It was the violence that made me feel as if I were suffocating in my parents’ histories. The intense, perpetual, disregard of human life. Of animal life. I had a neighbor who had a dog named Smoky. The neighbor was a kid, a bit older than me but younger than my older siblings, so perhaps 12 or 13 when I was 9 or 10. The neighbor had trained his dog, had trained Smoky, to attack Black people. He’d sneer, “sic”, whenever he saw a Black person and Smoky would chase the Black person, snarling and threatening. The neighbor only did this with the younger Black children, of course. One day, I was riding my bike, going very fast, downhill, and about to make a hairpin turn, past Smoky’s house, when I saw the neighbor and then heard Smoky’s barking, felt his spit on my ankles. I had a really bad accident. Crashed my bike and surprisingly didn’t break any bones, didn’t die. The neighbor hovered over me, laughing, as I tried to disentangle myself from the bike, tried to get away from the barking, the snarling, the snickering. Violence.

As a very young child, I wanted to know everything about the other side of violence for my parents. Who were those adults who survived Jim Crow? Who dared to lust? Dared to love? Dared to procreate? Dared to sing & dance & laugh & be joyful, to become autodidacts, to be regional historians, who integrated a White neighborhood in 1978. My parents sacrificed their lives to offer their children access to resources that they had been denied; placing us in White neighborhoods so we could go to White schools where the students were provided with updated textbooks, had computer programming courses by 1985, had both college prep & AP courses, had pre-ACT & pre-SAT prep on Saturdays, had field trips and guidance counselors, school nurses and playgrounds; a tennis court.

Despite all of this luxury, all of this access, Smoky’s human was being raised by White adults to despise Black people. Smoky’s human had a sister named Beth. She was a year older than me, my sister’s age, but my sister didn’t like to play with Beth so Beth played with me. When I was maybe 7 and Beth maybe 8, she knocked on the door and asked me to come out to play. I wasn’t allowed to go out at that time, for whatever reason, and I told Beth. When I moved to close the door, Beth called me a nigger. My dad, hearing this, invited Beth to our weekly Black History classes. Love. Beth came for one or two classes but afterwards, she stopped coming by altogether. When I later saw her, she said her mother didn’t want her playing with niggers.

Morrison’s novels showed me the starburst patterns of racial violence. She says in an interview that she wanted to write a novel that examined the question of self-loathing. What were the conditions that made a Black child loathe herself? I understand this question and the violence that undergirds the responses. But it wasn’t until I read The Bluest Eye that I was able to point at so many racial violences, including the ones we take for granted–billboards featuring “beautiful” White women; candy wrappers featuring “cute” White children, and the ways in which these violences were not the other side of Love, but completely antithetical to Love. In the South, we hear so often how Confederate-flag flying White people are not racists, but just people who Love themselves and their culture; how it’s Love that drives the cross in the ground; Love that sets fire to that cross; Love that holds the rifle; Love that pulls the trigger; Love that places a noose around a Black person’s neck; Love that hangs and maims and destroys. But in reality, its racial violence that, for example, kept Polly (Pauline Breedlove) from having access to, say, art education. Violence that kept Polly from becoming an interior designer or visual artist. Racial violence is America.

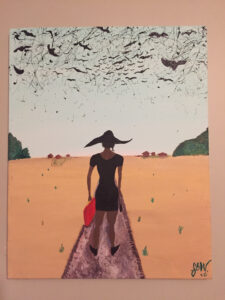

By the time I decided to get yet another Masters degree, I had read all of Morrison’s published novels. I read Jazz twice before I was able to appreciate it (and was only able to appreciate it after I spent a summer listening to jazz music and educating myself on jazz music). As a student in the Afro American Studies Program, I went a step further with Morrison: I began to read criticism about her work, interviews of her discussing her work. I would go on to write my own critical responses to her work, deciding, while writing my thesis, that part of what made Morrison’s work special and difficult is that her narrators are intellectuals. They analyze the story that they’re telling as they’re telling it. It’s like reading a dissertation and a story all at once. What could I say about her work that she herself wasn’t already saying in the work? And how had she learned to write in this way? Eventually, I abandoned that thesis project and instead wrote a chapter on Sula, but I continued to read Morrison, to re-read Morrison’s interviews, to share her work with students. (And, to be honest, the first time I read Sula and all the times afterwards, I thought: on Halloween I will dress up as Sula, because, really, I wanted to be Sula. A student, knowing how much I loved Sula, painted a picture for me, of Sula returning home and the blackbirds announcing her return.)

By the time I decided to get yet another Masters degree, I had read all of Morrison’s published novels. I read Jazz twice before I was able to appreciate it (and was only able to appreciate it after I spent a summer listening to jazz music and educating myself on jazz music). As a student in the Afro American Studies Program, I went a step further with Morrison: I began to read criticism about her work, interviews of her discussing her work. I would go on to write my own critical responses to her work, deciding, while writing my thesis, that part of what made Morrison’s work special and difficult is that her narrators are intellectuals. They analyze the story that they’re telling as they’re telling it. It’s like reading a dissertation and a story all at once. What could I say about her work that she herself wasn’t already saying in the work? And how had she learned to write in this way? Eventually, I abandoned that thesis project and instead wrote a chapter on Sula, but I continued to read Morrison, to re-read Morrison’s interviews, to share her work with students. (And, to be honest, the first time I read Sula and all the times afterwards, I thought: on Halloween I will dress up as Sula, because, really, I wanted to be Sula. A student, knowing how much I loved Sula, painted a picture for me, of Sula returning home and the blackbirds announcing her return.)

“Recitatif” is easily, for me, the most brilliant short story I’ve ever read. Its manipulations, its focus on the reader, on tapping into readerly bias and prejudice and stereotypes; all of it is so compelling. And, no, it’s not the best-written story; but it’s the best story. Who has read that story and is still not making an argument about who is who; which person is Black and which is White. And why, in a story that refuses us that certainty, does it matter? Why are we so compelled to fix that race.

I love Toni Morrison’s writing. I love what Toni Morrison’s writing has done for me, individually, as an intellectual, as a scholar, as an advocate, as an activist, as a writer, as an educator. I love knowing that Morrison’s mother’s name is a city, just as my birth name is a city; that our names were chosen in the same way, picked from the Bible, that neither of us like those names. And yet, that holding the name of a city, an ancient city, places a kind of responsibility on us. A kind of birthright or birthmark: to hold the name of a city is to hold people, language, food, beliefs, practices, knowledge, songs, dances, pleasures and delights, wars and ravishments, to hold dream and vision and to make space for many to build futures. Morrison’s work, even the work set in the past, builds futures. Yes, she’s now transitioning to another space, another dimension, but her work is here, always. Thank you, Toni Morrison.

Author’s note: The title of this piece comes from a Toni Morrison interview Emma Brockes for The Guardian.